London’s Tate Modern presents a sprawling exhibition that attempts to map Nigeria’s complex 20th-century history through its visual arts. The show, tracing the evolution of modernism from the colonial era onward, is as ambitious as it is unwieldy, reflecting the nation’s own fractured and multifaceted narrative.

The journey begins under the shadow of colonial rule. Early works include European-influenced portraiture alongside powerful indigenous carvings. One set of wooden door panels from 1910-14 depicts a British officer being carried aloft, a scene that inadvertently reduces the figure to a powerless homunculus. This is juxtaposed with historic photographs by Jonathan Adagogo Green, capturing deposed local rulers in their finery—images that simultaneously document and implicate the photographer in the colonial dynamic.

A central figure is Ben Enwonwu, hailed by many as a pioneering African art star. His career was remarkably diverse, spanning sculpture, painting, and education. Works on display range from a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II to dynamic watercolours of dancing women, exploring themes of Black culture and Negritude. His iconic sculpture Anyanwu, representing an Igbo mythological figure, exists in versions at the Nigerian National Museum and the United Nations, with a smaller model featured in the exhibition from the Royal Collection.

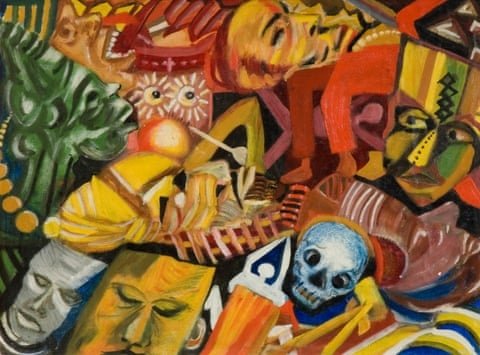

The narrative then shifts to the fervent period surrounding independence. In 1960, a group of art students, rejecting their Eurocentric training, formed the Zaria Art Society. Their rebellion led to the co-founding of the Mbari Club, a collective of artists and writers. The art from this period often carries a raw, urgent energy. Uche Okeke’s paintings present monstrous figures and scenes of cultural conflict, while Demas Nwoko’s Nigeria in 1959 serves as a chilling premonition, showing uneasy colonial officers overseen by menacing Nigerian soldiers.

Attempts to evoke the cosmopolitan atmosphere of post-independence Lagos, through architectural photographs and Highlife music, feel underpowered in the gallery space. More compelling is the work of the Oshogbo School, which drew deeply from Yoruba mythology. The artist Twins Seven-Seven created electrifying, densely populated canvases teeming with spirits and imagined cityscapes, his own remarkable life story begging for a fuller telling.

The exhibition’s penultimate room is dominated by the poetry of Christopher Okigbo, who died fighting in the Biafran war. His words, “The smell of blood already floats in the lavender mist,” echo through the space, casting a sombre pall over the art and artefacts.

This sense of unresolved history permeates the final gallery, dedicated to Uzo Egonu, who spent most of his life in the UK. His paintings of London scenes possess an anxious, sinister calm, his figures trapped in a geometric, strangely static modernity that feels both universal and placeless. It is an abrupt ending for a story that feels far from over, leaving visitors with the impression of a national narrative still very much in flux.